INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE AND LANGUAGE OF WOMEN FARMERS IN AFRICA; HOW THINGS WERE, HOW THEY ARE NOW AND POSSIBLE FUTURES.

Indigenous knowledge.

Simply put, indigenous knowledge is a combination of human mental and practical knowledge, in most cases unwritten or undocumented. This knowledge has been passed by, and acquired from, one generation to another inform of stories, songs and practical forms (skills) by old to young ones.

Indigenous knowledge is developed and maintained in an open system of exchange, reciprocity and dialogue among communities and within nature and from the more than human(Spiritual) sources. Indigenous knowledge is acquired from a holistic life long, non-formal education system intended to help the learner grow better and responsibly in a social, cultural, spiritual and ecological environment.

Indigenous knowledge embodies profound ecological knowledge that includes both specific knowledge on the diverse species of plants, soils and seasonal cycles, as well as an understanding of the dynamics of the ecosystems with which they have co-evolved overtime.

Globally, there is a growing recognition that indigenous and traditional cultures have a wealth of knowledge and capacity for protecting landscapes and seascapes and navigating challenges of climate change (Raygorodestky G.2011).

However, indigenous knowledge has suffered a big blow from colonization which recognized modern written/documented knowledge and ignores the age-old-unwritten one. It is often disheartening when modern knowledge has demonized traditional cultural knowledge, even when it is clearly seen that most of the latters’ aspects are borrowed from the former.

Women farmers and indigenous knowledge

Over millennia women, in most African traditions, have played a central role in passing this knowledge from one generation to another because of their strong connection and love for nature. Indigenous women in Africa have maintained this knowledge by sitting closely with their children, especially girls, telling them stories and secrets of a woman and relationships with nature. Women, especially rural women who are farmers, have played a big role in selecting, breeding storing and sharing indigenous seeds. They have been responsible in enhancing the diversity of their seeds.

Indigenous knowledge has evolved over generations. This knowledge lies at the heart of women’s continuing role in building resilience and their status in the community. However, due to African colonialisation and consequent introduction of western education system and industrial agriculture, the indigenous knowledge has been greatly affected. Where this knowledge still exists, it is faced with a lot of pressure from the so called “modern farming” and commercial agriculture.

AFRICE has worked with rural women especially those in traditional communities of Buliisa, Rukungiri and Kalangala. Our experience has helped us learn more about these women whose life has entirely depended on farming of indigenous seeds, both crop and animal seeds. In many indigenous and local communities, in Africa, especially Uganda, women have systematically used this knowledge and transferred it to their children in non-formal settings both through practical farming in gardens and theoretically at home.

- Selection of seeds

To produce food for their families in various conditions, women developed a sophisticated capacity to understand their ecosystems and the climate, making very accurate calculations as to what to plant in the coming season. The complexity of this knowledge system, the intimate relationship that rural women tend to have in the land and seed, and their understanding of the range of needs of the family and the community cannot be underestimated.

Women select seeds with great care and wisdom when they want seeds for different purposes. Their seed selection depends on its source and origin, the cook ability of the seed, its resilience to different conditions, its taste and the type of soil it will be grown, its nutrient and medicinal characteristics and the seed’s cultural or ceremonial functions. Other criteria is how fast the crop grows versus the different seasons. In Banyankole, a sweet potato variety that takes less than three months to yield is called Kweezi kumwe, literally meaning; one month.

The seeds’ source and purity counts more to a woman. More often, a woman will always get a seed from her store (granary) for planting. This seed will have been planted for several years and under gone specific rituals before it is planted in the garden. A woman will be very conscious to ascertain if this seed has gone through specific rituals lest it brings misfortune to the household or it fails to germinate, yield well or affects other crops with which it is grown. That’s why a woman will be inquisitive to know whether the seed is ‘’pure’’ if it is not the one from her granary. Traditional women farmers will not just pick and plant a seed from a source they do not know or are sure about. This is the reason why a woman will plant a seed from her mother, a sister, an aunt, grandmother or a very trusted longtime friend.

Seed rituals in indigenous communities vary from a tribe to tribe or a clan to another. The rituals are administered by either the woman, her husband, boy or girl child. Mother in laws, among the Bagungu culture and even others, are responsible for providing a seed to the newly married daughter in law. A seed that has not come from the mother in law would also be subjected to some rituals before she is allowed to plant it. In some communities a woman will be given a variety of seeds by her mother as she goes to have her family.

The meaning of all this is to maintain the originality and good qualities of a seed.

Some of the indigenous seeds and traditional herbal medicines

Some varieties of seeds are selected because they are sweet, they are eaten together with a given type of food or they grow as pure stands without long tendrils that cover other crops.

b) Maintaining crops in the farm and harvesting.

Preparation of land well in time for planting. There have been complaints of failing or poor yields in some areas or in some seasons of late. Many factors may be responsible for this but also the failure to prepare for the planting season has contributed to this. A traditional farmer, especially a woman knows the season when to plant what crop and where.

Observation and critical analysis of the entire weather, climatic and ecological behavior helps the farmer to determine when to prepare which seed, what form of activity or action should be done to the land, and what aspects to observe to ensure the land is ready for planting the seed. More often these days, farming is done by young women or men who have not sought guidance from their seniors. There is misconception that all we need to know to be good farmers is from extension workers advise or from the metrological centers.

Planting different crops (inter cropping) in the same garden at the same time but with different maturity periods. My mother, whom I used to go to garden with, never went in any formal school. We used part of our land for animal farming and another for crop growing. Apart from the sweet potato garden which was mono cropped (for reasons I never knew) most of the crops were inter cropped. You would find about seven types of crops in the same garden. This, I came to learn that the growth, feeding, resilience to pests and diseases and climatic conditions, the harvesting and storage characteristics of each crop are different, but all planned before the planning stage.

Pest and disease regulation technologies

Pests and disease are part and parcel and common to all plants and crops. Indigenous farmers regulate and control their incidence and impact on crops but do not eradicate them completely. Some pests are biologically and ecologically important to a crop at one stage or the other. Some pests feed on others while others, although feeding on a crop, feed on others which would otherwise be grossly harmful to other crops in the garden.

Farmers have learnt to treat or regulate some pests with different practices, ranging from mixing herbal concoctions, application of animal waste to planting plant repellants with in the garden or alongside the garden.

The attack of the safari ants to a garden always is a blessing as they will eat or carry with them all pests at any stage! Some birds also are very useful as they feed on many pests in the garden. The Bagungu women in Buliisa and Banyabutumbi in Rukungiri along L.Albert and L.Edward respectively, will use a skin of an animal or the water used for washing fish to scare away pests and stop some diseases from attacking crops.

In animals, a range of indigenous knowledge practices have been applied to reduce the impact of ticks and other diseases, including drawing blood from a sick animal with an arrow.

Regular garden monitoring of the crops in the garden is a daily routine of a woman farmer. It is not common for a woman to spend two days without visiting her different crop fields, and so does a man to his animals/crops. Regular monitoring allows a farmer to notice how particular crops grow, which are sick, which need support, crops that need to be removed so that they don’t infect others. Some pests are manually killed or removed from the garden and something is done (traditional belief) on it that will scare away other pests.

Crop rotation and bush fallowing are some of the ancestral methods for regeneration, pests and disease regulation, ensuring nutrients recycling and minimizing the rate of soil degradation and nutrients loss.

Communal gardening is a traditional practice that is dying away in some communities and yet was a practice that combined women energies at different stages of farming. Crops like millet, sorghum and others which are labor intensive at planting, weeding and harvesting call for communal work. During this communal working at the garden, the spirit of socialization is enhanced. Communal gardening is a platform for transmitting knowledge to young women and old girls who are involved in the activity. The knowledge passed is diverse; ranging from family, sexuality, agriculture, food preparation to feeding science.

Communal work, especially in millet growing, women harvest it in turns and whoever did not plant millet for some reasons but participated in harvesting in your garden will get seeds to grow for the next period.

Application of manure from animal droppings and kitchen products. When I was growing up, I would follow my mother in the banana plantation and see her carry and apply all kinds of animal waste, including; chicken, goat, and cow droppings.

She would also get human urine, after keeping it for some days, and apply it on banana stems to protect them against banana wilt. Later, when I started working with women small holder farmers, I found it was a practice, and many others, common to their knowledge. It is what is now called agro-ecology!

d) Knowledge about wild food relatives.

In all local and indigenous communities, it is not uncommon to find young children, even women, in the bush collecting different varieties of mushrooms. The common and communally gathered mushrooms are the small white variety (obutuzi) which, as a traditional norm, no one can pick them alone. It has to be a group or a whole village. There would be a house hold which identified the anthill with signs of the young mushroom and then put a coil made of grass- a sign that no one else will claim the identification which was called okwiita literally meaning “making a kill”. Thereafter, a young girl or boy would be sent around by the mother to invite the rest of the village, especially the immediate neighbors to pick together. It was a mentally documented case against any household which picked the mushrooms alone. It would be a shameful village talk around that so and so is greedy, selfish, uncooperative and should be punished in a way for “eating alone”

There are very many varieties of mushrooms picked from the bush, especially during the rainy season. They are nutritious and medicinal at the same time.

Other forms of wild food include fruits from wild trees and shrubs, white ants, grasshoppers, etc. which communities eat as delicacies and additional food during the lean season when planted food is scarce. These foods enhanced biodiversity protection because bushes and some plants would not be destroyed, lest community food is endangered.

Increased biodiversity loss has resulted into disappearance of most of these wild food varieties.

e) Food storage.

The storage is pre-planned; Harvested seeds are mainly stored in granaries made of local plant materials. The granaries are kept for long and repaired when they are damaged in any way. Different shrubs are used during smearing the granaries to make sure vemine and pests are stopped from entering or eating the seeds.

Some crops, e.g. tubers like cassava, potatoes, yams, pumpkins are stored in the gardens and picked for a meal when they are needed. The indigenous varieties of these remain in the soil for more than 2years, especially cassava, yams and potatoes.

Some seeds are stored above the local fire place (fire stones) for making it difficult for pest attack, especially maize seeds.

f) Traditional climate prediction mechanism.

Not any seed or seed variety is planted in any season. Women know which seed is planted in short rains, long rains or during both seasons. More often, these days, inexperienced farmers grow wrong seeds in inappropriate seasons and end up not yielding or being hit by heavy rains or heavy sunshine.

Traditional climate prediction is an ancestral way communities have been able to tell, for example, if it will rain, if there will be a lot of rain or little, if the next season (dry or rainy) is approaching or the current one is about ending or continuing.

Prediction of these climate or weather variations differ within geographical locations. Also, some of this information (as passed from generational to another) is based on different cultural beliefs, physical weather phenomenon and natural behaviors.

The direction of wind, whether wet or dry, fast or violent and its timing explains, for example, the coming of rains, its likely form and type.

Traditional seasonal calendars

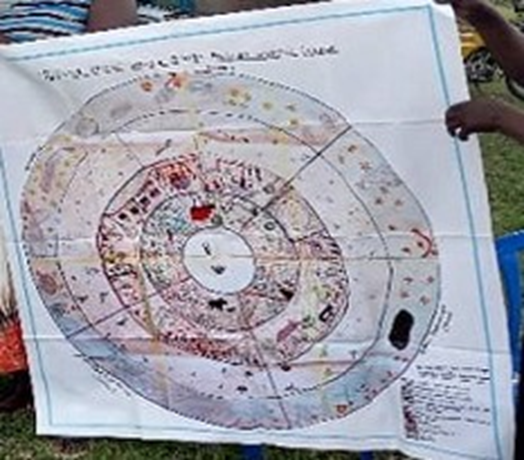

The Bagungu women custodians of indigenous seeds in Buliisa, Uganda, during the initial dialogues about reviving their seed knowledge, drew what is called traditional seasonal calendars.

a) The ancestral calendar

This is a visualization of the ancestral order which was very informative due to the stability of climate, with slight variations. This calendar is a presentation of what was happening more than 50 years ago when the natural phenomena were aligned and coinciding with respective seasons namely; the dry season, mini-dry season, mini-wet season and very wet season, according to the Bagungu cosmology.

The ancestral calendar is a manifestation of less human destruction of biodiversity, stable and predictable climate. The state of affairs allowed relative accuracy in climate prediction.

The Bagungu people’s ancestral(Past) calendar dating (2018) –backwards 50 years ago.(Africe file Photo)

b) The current Calendar

The second calendar is the current condition where human activities altered the natural phenomenon. The destruction of biodiversity, human activities in form of settlements and agricultural activities have destabilized both the natural order of events at the 4 levels. The seasons and respective expected human activities have changed, leading to inadequate farming activities and farming outcomes. However, the Bagungu women still use some of this knowledge to predict the likelihood of what would happen despite the changes resulting from human activities.

c) The Future Calendar

The future calendar is a “wish” calendar; where the community would want to see if the prediction mechanism has to work, some irreversible situations notwithstanding. The calendar shows that if the human behavior could change and some activities follow laws of Nature, the mechanism would work again, enabling smooth farming circles.

The Bagungu People’s future calendar,2018 and on wards (Africe file Photo)

Indigenous knowledge on medicine:

Other forms of women indigenous knowledge systems

Handicrafts, pottery, basketry and different forms of weaving is traditional knowledge held by women farmers in Africa. The decline of this knowledge due to modern industry and technology has seen the introduction of the current harmful plastic materials on the market and in household usage.

Wetland materials like, swamps, papyrus provide raw materials for traditional handicrafts. Less of these wetlands would be destroyed if women were valuing them as their source of income.

How is it now?

In most indigenous and local communities, indigenous knowledge is being practiced. As already mentioned, the more communities are exposed to modern and commercial farming the more this knowledge gets lost.

The formal education systems in most of African countries puts much focus on theoretical farming knowledge than the practice as the traditional knowledge systems. Children who are brought up in, and educated in the urban settings are completely disconnected from this knowledge. Where practice is done in some institutions, little about this knowledge is applied, leaving out the social cultural aspects of food and farming. After all, most of the teaching and training materials are developed by experts trained in foreign languages.

The diminishing traditional cultures due to long term suppression are going away with traditional/indigenous knowledge in farming.

This knowledge is more effectively applied in a more ecologically stable natural and social environment. For example, women find it more difficult to make traditional climate and weather prediction in a situation where biodiversity has been lost.

Agroecology is a farming system that borrows much from indigenous farming systems. In formal educational system, the instructional materials and language used to deliver this knowledge are foreign to the farmers.

What is the possible future of this Knowledge?

As already mentioned, farmers are now getting to terms with reality; modern farming knowledge is betraying them and are finding indigenous knowledge the best alternative where the conditions are favorable. For example, in traditional communities where households produce enough seeds, these storage systems still apply. because they are most effective and safe for seeds.

The rest of the Knowledge practices; like seed selection, breeding, pest and disease control, and wild food collection (wild relatives) are being threatened to extinction. More and more of the knowledge is being replaced by industrial and commercial farming knowledge. Unfortunately, commercial/industrial knowledge systems have assumed and behaved as if communities did not have food systems before. Modern farming systems should embrace traditional /indigenous systems, especially as those recognized by agro-ecology if our food are to sustained and sustainable.

Issues to reflect upon;

- Documenting or not to document indigenous farming knowledge but emphasizing practice.

- What is the effectiveness of enforcing indigenous farming knowledge policies/education?

- Where the indigenous farming knowledge is not practical/possible what adjustments/alternatives are available?

Banyabutumbi women harvesting millet at the demonstration garden at the Community seed learning center in Kikarara Rukungiri District,

Photo: By AFRICE, 2020

- An article published in The New vision paper in December, 2020 where Buliisa District Council passed the Ordinance to protect the Sacred Natural sites and Ecosystems in Buliisa District.

- Bagungu women (custodians of indigenous seeds) displaying their locally made granaries. These granaries help in the food storage, seed preservation and seed saving for the next planting season. Indigenous seed storage has helped them address the issue of food insecurity in their communities. Photo: By AFRICE, 2021.

- The Banyabutumbi indigenous women make organic manure and organic pesticides using local herbs. Photo by AFRICE, October,2021

- A young woman (Uwihoreye Ricky), a member of the Banyabutumbi indigenous community in Kikarara demonstrating how organic pesticides are locally made (see below also) Photo by AFRICE; October, 2021

- The Banyabutumbi small holder indigenous farmers at Kikarara, Rukungiri district in their demonstration garden at “Iganiriro Rya’Kubumbu,” Community seed learning Center. The Banyabutumbi use traditional farming systems and have recouped some once lost indigenous seed varieties which they are now multiplying and sharing with the rest of the community. At the center, elderly women train the youth in traditional seed identification, seed breeding and storage. Organic pests and disease control using local knowledge is also practiced at the center. Community members come to learn and replicate the practices at household level.

Photo by AFRICE; October, 2021

- A locally made Banyabutumbi granary (Ekitara) at the seed learning center in Kikarara village Rukungiri district, each one of the major crop, i.e., maize, millet, sorghum, groundnuts etc. (cereals) has a particular type of a granary (Photo by AFRICE;2021)

- See below. Photo: By AFRICE

- Mrs Kagole Margret and some of the custodians of sacred Natural sites, drawing an Ancestral map in efforts to locate Sacred Natural Sites, ecosystems and territories in Bugungu ancestral land. The custodians did this work; Eco mapping, during the process of reviving their customary governance systems in order to secure and protect their Natural and cultural heritage.

- Sacred Natural Sites are important ecological and cultural areas, home to different forms of biodiversity, globally recognised as community conserved areas and no-go- areas for industrial and other human activities. Photo by AFRICE

- An old woman (Nyigesha) a member of Banyabutumbi using locally made pesticides to spray her crops in the garden. Photo by AFRICE

- Bagungu Custodians of sacred Natural sites in Buliisa after the meeting to validate contents of the ordinance for protection of sacred natural sites and Ecosystems in Buliisa. The ordinance also comes into effect as a strategy to implement the Rights of Nature as enshrined in Section 4 of the Environmental Act in the Uganda National Environmental Law (2019).

- Photo credit by AFRICE (December,2020)

- Mrs. Kagole Margret from the Bagungu community women group,” Tulime Mbibo Zikadde” in Buliisa, showing Dennis Tabaro (the Executive Director of AFRICE), one of the different types of traditional and locally made granaries(Mutogooro) that are used for food and seed storage in their communities. AFRICE accompanies these communities as they strengthen their cultural practices for conservation of food. The granaries have helped communities to store enough food for both household consumption and seeds for planting in the next seasons. Photo by AFRICE; 2019

- Some of the recouped indigenous seed varieties among the Banyabutumbi and Bagungu communities in Rukungiri and Buliisa respectively. Indigenous seeds play multiple roles, ie provision of Nutrients, medicine and cultural functions.

- PHOTOS: By AFRICE, 2020.

Tabaro Dennis Natukunda is the Executive Director of AFRICE,

Dennis is a professional Agroecologist and Earth Jurisprudence Practitioner.